Another beautiful day in the pā. I’m always learning more about my harakeke as I work with it and observe its nature. This last pā of this variety hasn’t been harvested since I first planted it, which explains the build-up of pakawhā.

When a pā is overgrown and built up with excess leaves it can be overwhelming to clean because it is so dense. I have learned to just slowly work my way from the outside in one bit at a time taking time to stop, rest and plan my next step. Also to enjoy the process and the observation of whats happening within the pā.

with this pā I did things a little bit different because my other knife was dull and so I used this sickle tool which started off sharp and went dull toward the end. Anyways its too big of a tool to get right down to the base of the leaves so I cut higher up then after I went back with my other knife to cut all the way down at the base leaving all these short take pieces to pick up at the end. Im definitely not doing that method again so I need to get my knife and sharpening skills in gear.

Today we commonly use rau to refer to all kinds of leaves however the actual term for leaves belonging to harakeke and similar plants is whā. Within the whakapapa of harakeke, Pākoti or Whākoti is the mother of Harakeke—he māramatanga kei roto i ngā ingoa. There is deep insight in these names.

Huna is the personification of Harakeke. The word means to conceal, to hide, to be unnoticed. These qualities speak not only to Harakeke’s physical nature, but also its metaphoric one. The more time you spend in the pā, the more these kura huna—hidden treasures of knowledge—begin to reveal themselves.

One of my favourite Hawaiian proverbs is: ma ka hana ka ‘ike—in working, one learns. I love this because I believe words alone often fall short of expressing the true depth of ancestral knowledge. But through doing—through the mahi—understanding is unveiled.

Ko te putanga o Uenuku hei whakakapi i ngā mahi o te rā.

The appearance of Uenuku brings closure to the labours of the day.

The weather has been beautiful and warm here in Te Tairāwhiti, so I’ve been able to get a lot of cleaning done—no rush, just slowly working away. My last blade is dull now and giving me a wonky angle on my cuts, but I’m not about to drive 20mins into town just for that. I’ve been meaning to switch to a knife I can resharpen myself, but I haven’t found one I like yet. Once I’ve cleared out the bush, I’ll come back through with a sharp blade to tidy everything up—I like my pā to look nice.

I also need to pull the grass back. I’ve noticed notch moth has settled in due to the overgrowth around the harakeke, and mealybugs too—it’s just become too congested. This is a year’s worth of growth that’s been waiting for me while other mahi has pulled me away. I do feel a bit bad about that, to be honest.

This variety of harakeke grows very fast and sends out new shoots prolifically, which is great because it quickly forms a pā (cluster). The downside is that once it’s mature and well-established, it becomes extremely dense, and the whānau need to be removed to make space for new growth. These whānau also have a long life span before they flower and die.

I have other varieties that were planted at the same time, but they’re much smaller and haven’t multiplied in the same way. These pā are now seven years old and have grown from five clusters of three tipu each, spaced about six feet apart. I’ve mentioned this process briefly in other posts

When cleaning I start in one spot and remove whatever is within reach. I don’t try to go too far in, as I know I’ll be circling around the patch anyway. It gets really dense in the center, and it’s hard to maneuver a knife in there so I cut what I can and carry on. Things will open up along the way and can get the tricky ones later.

Continue reading in the comments below⬇️

Over the past few weeks, as I mentioned in my recent stories, I’ve been tying up my last project. This has involved a lot of writing, organizing photo and video documentation, filing things away, and a bit of website maintenance(which drives me mad)—along with other business tasks that, while not the most exciting, are necessary. Admin work isn’t my strongest suit, but I’m pushing myself to get better at it because it supports the continuation of this mahi.

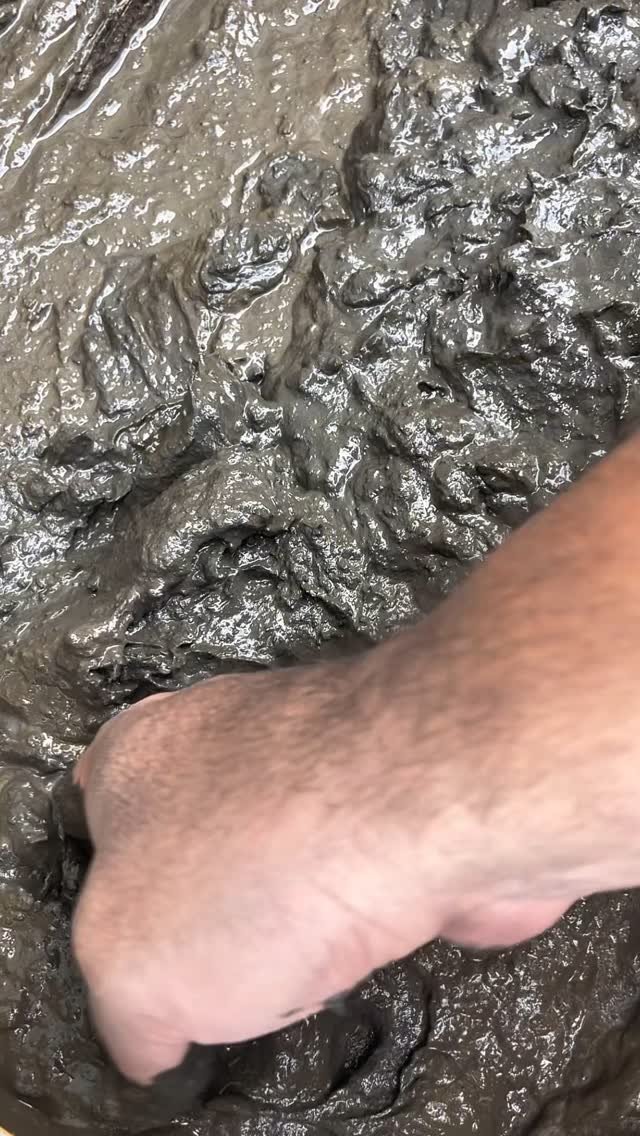

While I have been taking care of that stuff, I’ve had this blue bucket sitting on the back porch—the one I used to rinse paru (iron-rich mud). I left it out so the water would slowly evaporate, leaving just the mud behind. After a few weeks, it finally returned to its thick, muddy state. In the past, if I was in a hurry, I’d just wait for the mud and water to separate and pour the water off. But it’s much better to let the water evaporate naturally, as it keeps all the valuable minerals and elements within the mud.

Ideally, I prefer to do this dyeing process at the source, so everything returns to where it came from. But when time is tight, I work with the tub of paru I keep at home. When working this way, it’s important to return as much of the mud back to the tub as possible. Why? Because this is a precious resource for weavers—it’s not found everywhere. Caring for it ensures it remains available for future generations. In this case with the tub if I look after it as I should, I will never have to return to the source to get more.

So, to quickly recap the process if you’re dyeing at home using a tub of paru:

Read further in the comments⬇️

852.He ‘ohu ke aloha, ‘a’ohe kuahiwi kau’ole.

Love is like a mist; there is no mountain that it does not settle upon.

Love comes to all.

‘Ōlelo No’eau

Hawaiian Proverbs

Another one of my favourite photos—

me in the garden at our home in Lā’ie,

wearing a papale(hat) I wove from the leaves of our hala trees.

Trees my sister Arihia and I planted together, many years ago now.

I tied a red ribbon to it and secured it beneath my chin—

the only ribbon I had—

to keep the wind and branches from knocking it off.

A practical fix, and soft against my skin.

Most people save their papale for special occasions—

I wear mine here, doing things like this.

This is the occasion.

Probably my favourite photo of me as a kid.

1996, Kauaeranga Valley.

Nature has always been where I’ve felt most like myself.

As the years pass, my childhood comes into clearer focus—

and with it, a deeper understanding of who I am.

For a long time, I struggled to see how my life led me to this path.

I used to wonder why—what was the connection?

But as I’ve grown into myself—as a ringatoi,

and as someone willing to look back through my own lived experience—

it all makes sense. How could I have ended up anywhere else.

Over the past couple of years, I’ve had conversations with my mum and aunties—

It often starts with them expressing how proud of me they are and so I remind them: you all created this. They look at me confused.

I grew up surrounded by makers.

Everyone in my parents’ generation—and those before—was deeply skilled.

Knitting, sewing, gardening, building, cooking, playing music, singing—

you name it, they did it all.

But when I talk to them about it, they don’t see it as being special or artistic.

To them, it was just “making do”—doing what needed to be done to provide for the whānau, for the hāpori.

My mum sewed her own clothes, and ours too,

up until a certain age. She was still making her clothes up until last year. Growing up she he was always transforming our home—reupholstering, making curtains, redecorating—

and yelling at all six of us to keep everything spotless. Our home was always beautiful.

The same amount of care and attention was given to the gardens. Most people in the community had grew fruit trees growing, lemons, feijoas, plums, apples, loquats, passionfruit. All kinds of fruit trees around.

Every summer, camp on our whenua,

on the shores of Taupō-nui-a-Tia,

with a clear view of Tauhara rising across the water.

On our drives, Mum would recount stories of growing up, about people, places and whakapapa. Some stories I loved listening to while others not so much. The stories were told the same every time, word for word. By the time the fourth word is uttered you know what story was going to be told.

Though times have changed I still cherish and honour the beauty created by those people,many now past on.

Reflecting on this beautiful journey with you all.

@fordfoundationgallery Lisa Kim

@brianpolymode @siborg81 @_randahadi @krisnuzz @marythemaxxinista Jamie Kulhanek

@papahanakuaola @kahiauness @olivia.wa

@roderickpudigon @iraia_bailey , Māmā & Pāpā, Uncle Steve

@kapoinabailey

Nui te aroha ki a koutou katoa❤️

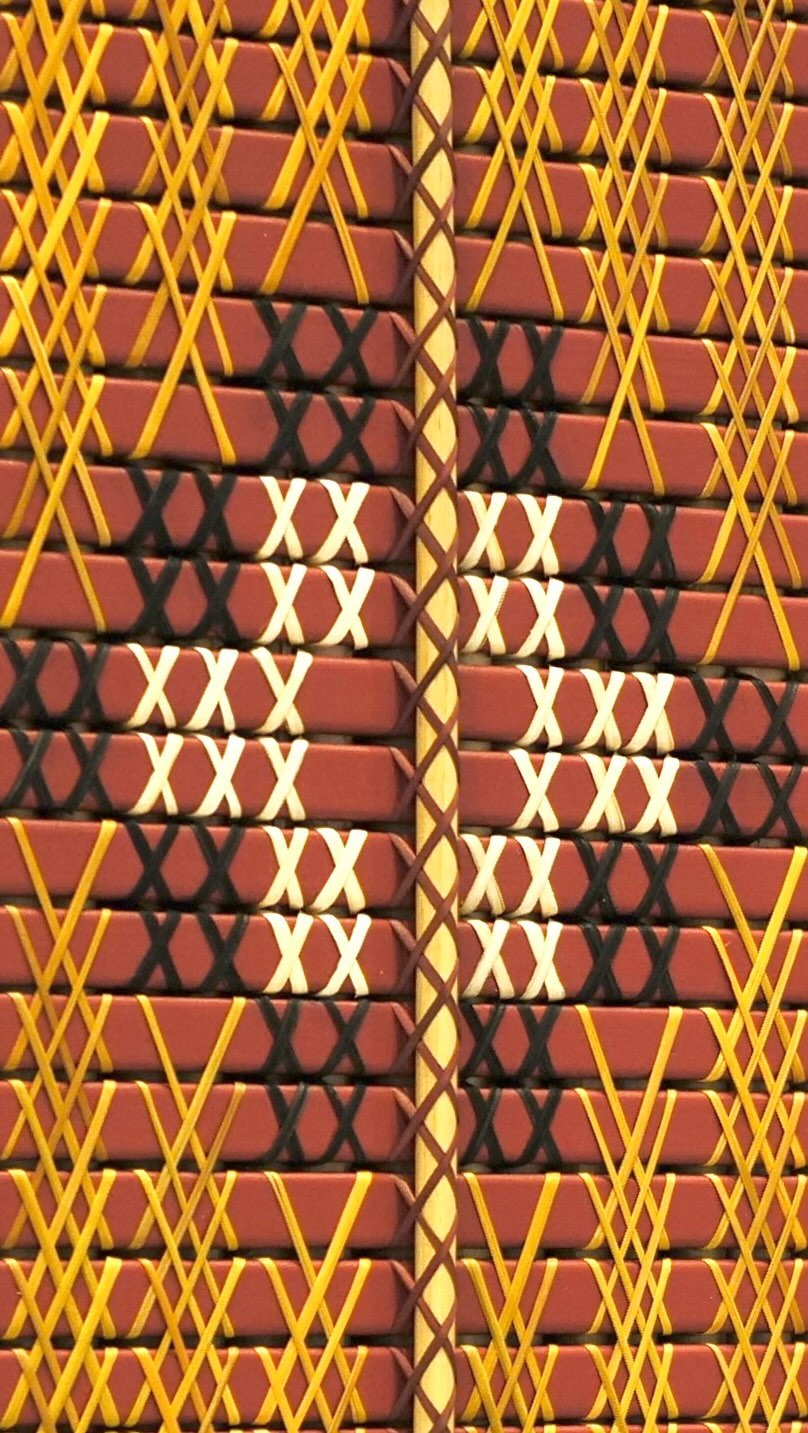

Māra Kūmara a Ngātoroirangi

These tukutuku panels, named Māra Kūmara a Ngātoroirangi by my tuakana Irāia Bailey, pay tribute to the great leaders of Te Ao Māori—those who planted the seeds of change, nurturing generations past, present, and future. As we harvest the fruits of their labour and sacrifices, we too continue the cycle, planting seeds for those yet to come.

The kūmara (sweet potato), a staple food of our people, serves as a metaphor for this enduring legacy. The patterns woven into these tukutuku embody the histories, genealogies, and cultivation practices that connect us to our ancestors.

The golden bindings symbolize Māra Kūmara a Ngātoroirangi, a name also given to the altostratus clouds that stretch across the sky. Ngātoroirangi, the esteemed ancestor of Ngāti Tūwharetoa, is credited with bringing abundance to the Taupō region:

“Ko taku tūpuna ko Ngātoro

Hei rū kai ki Taupō”

(‘Twas my ancestor Ngātoro,

Who scattered food throughout the Taupō country.’)

The three diamonds within the tukutuku represent Te Kūmara Nui a Mataora, a constellation guiding the planting and harvesting of kūmara. The key stars—Pani-tīnaku (Deneb), Poutūterangi (Altair), and Whānui (Vega)—mark the seasons. According to our pūrākau and whakapapa, Pani-tīnaku is the mother of the kūmara, her rising in October signaling the time for planting. Whānui, the deity of kūmara, appears in the northeast around April, heralding the harvest:

“Ka rere a Whānui, ka tīmata te hauhake.”

(‘When Vega rises, the harvest starts.’)

Through these tukutuku, we acknowledge the wisdom of our ancestors, woven into the land, the sky, and the stories that continue to guide us.

@fordfoundationgallery @polymodestudio @bipocdesignhistory @brianpolymode @siborg81

@papahanakuaola @kahiauness @olivia.wa

Photos by @roderickpudigon

It’s been beautiful to be back in Hawai‘i after a busy trip away. Over the past few weeks, I’ve had the chance to rest and reconnect with ‘ohana, friends, marae, and the community. This week, our good friends down the road at @hoalaainakupono invited us to join them during their spring break keiki/‘ōpio program, Ho‘āla ke Kilo, to capture photos and videos of their work. This ‘ohana played a huge role in helping me create the tukutuku in gathering the natural resources, so having the opportunity to give back since returning has been important.

Based in the ahupua‘a of Kahana, this program focuses on strengthening the Kahana community—by fostering deep connections (pilina) with the environment, ‘āina, and kai through cultural practices.

Right away, I was blown away by these keiki and ‘ōpio. Not long after we arrived, the young men set off with their net, and within five minutes, they had brought it back full of āholehole. Without any instruction from adults, they instinctively worked together, from oldest to youngest, to remove the fish from the net. I had a feeling to follow them to record them casting the net, but I honestly thought I’d have time to catch up—turns out, they were too fast!

As we worked to remove the fish, I asked them about what they were doing, and they confidently explained the process to me. Once the fish were removed from the net, they were taken to the muliwai(estuary) where they were caught, where the first step—of course—was taking a picture of the catch. Then, they washed and prepared the fish for descaling and gutting. Everyone joined in, from the keiki to ‘ōpio, with their ‘āina as their backdrop. Everyone was focused on their work with scales flying all over the place. All things connected.

One of the oli(chants) that was chanted during piko(opening protocol) names the mountains that border Kahana and as we were working I stepped back and noticed we could see all of these mountains from where we were standing at the loko i’a (fishpond). These ancient structures are designed to optimize natural watershed patterns, nutrient cycles, and fish biology of which I am still learning about.

Continued in comments⬇️